New Phase: Day One

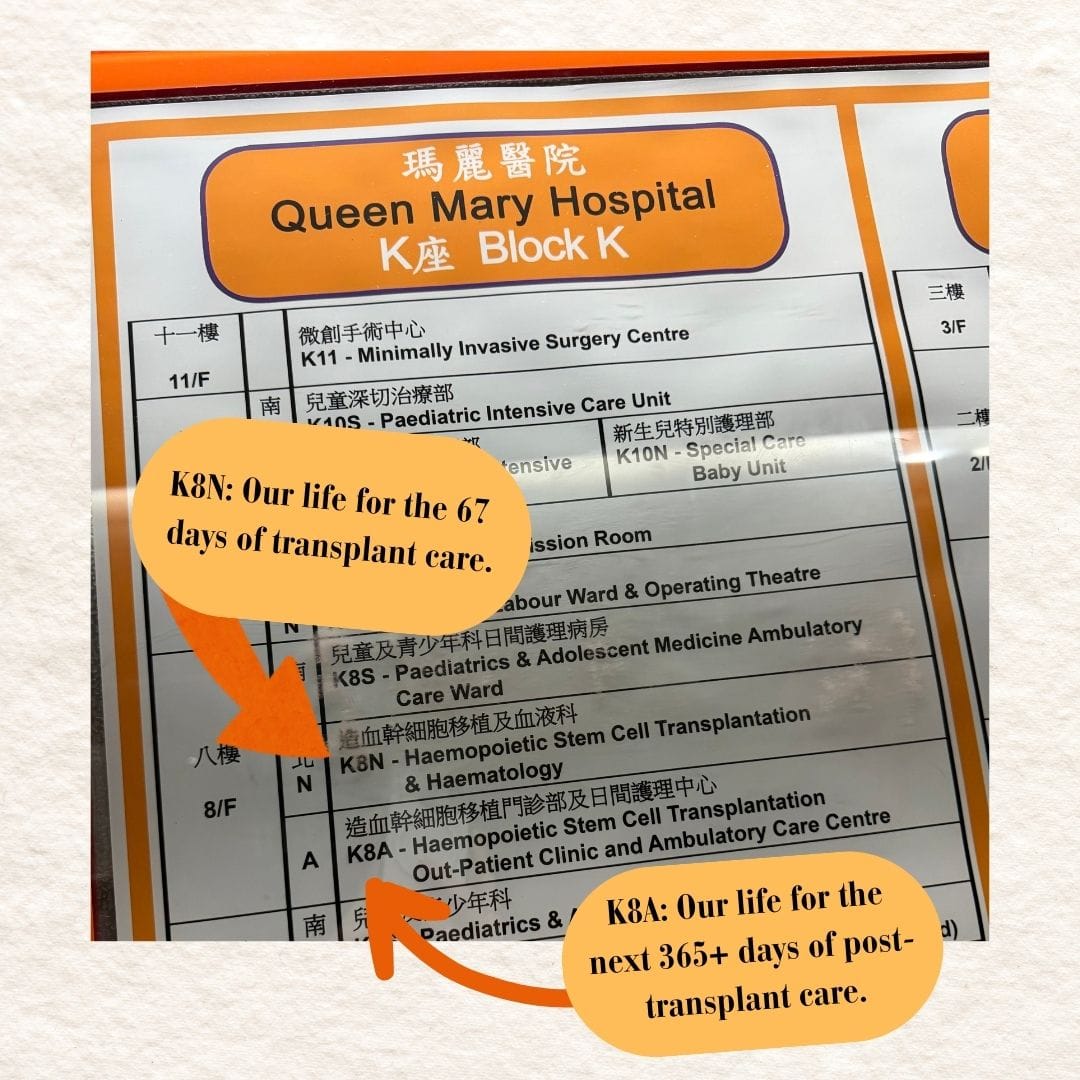

We’re out of the Isolation Ward and into the Out-patient Clinic. It’s been a bumpy transition.

Michael was released from the Transplant Isolation ward a week ago on Friday, which was a relief and cause for unrestrained celebration for about one full day. Then the stark reality of the newest phase of this journey through Acute Leukemia set in.

When our youngest son Benjamin was born, he was whisked away from us to the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) pretty quickly. They detected a loud heart murmur and noticed his lips and fingertips were taking on a bluish tinge. He had congenital heart disease which had been missed in every single prenatal ultrasound. He was transferred to the Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford University, where he would ultimately have heart surgery at the tender age of four days old. Friends who visited recount walking past the rows of isolettes filled with tiny micro-premie newborns to get to Ben, a relative moose weighing nearly nine pounds (4kg) at birth. I don’t remember any of that, I only had eyes for our own baby, overwhelmed with physical pain from my C-section. What I do remember was the day they disconnected Benjamin from all the wires, tubes, monitors, and alarms and sent us home alone, unsupervised, with this fragile new human.

It was overwhelming to go from round-the-clock intensive care in the NICU to our home which had only two very tired parents and a remarkably healthy toddler who had never been to the doctor except for well-child checkups! This current time we are in with Michael feels a whole lot like that. We are undertrained, unequipped, exhausted, and overwhelmed. I naively thought things might be easier, but the truth is we are not in an easy situation — we just need to keep growing stronger. And as my dear friend Melissa reminded me on the absolute worst day of the transplant period when the sights and sounds of hallway outside the isolation ward were threatening to swallow me and my tender heart right up: there is provision for you here. We can do this, hard as it is. We are not alone.

It’s been a hot minute since I tracked everything I did in a day on my phone’s note app, something I did several times when Michael was first diagnosed. Everything was new and strange and I wanted to capture it before it had a chance to become “normal” and therefore forgettable. As last Monday, August 25th, began the newest phase in Michael’s care, I decided I would jot notes on my phone just to remember what our first day back at Queen Mary Hospital, post-transplant in the Outpatient Clinic was like. I’m glad I did… it was a very bumpy ride with lots of tears (from both Michael and myself). Halfway through the day I messaged Benjamin an update, concluding with one day I’ll look back on today and laugh at what amateurs we were on the first day. Sigh. May it be so!

I invite you to join us on the first day of this new stage of Michael’s life post-bone marrow transplant. As a testament to just how rough this new phase has been, please know it’s taken a full week to edit this, working on it every single day in the very few “free” moments I’ve been able to find.

Monday August 25, 2025 — eight months and one day since Michael was diagnosed with Acute Leukemia.

5:15am I wake coughing from a dream where I feel like I’m being choked. It’s still dark outside. It either wakes Michael or he’s already awake and rolls out of bed to use the toilet. His alarm was set for 5:30am, my alarm will go off at 5:45am to give him extra time in the bathroom. I lay very still, trying to consciously absorb extra rest ahead of a busy day.

5:45am Michael is done in the bathroom so while I brush my teeth, slather on sunscreen, and swipe on mascara, he gets dressed. None of his clothes fit. I ran to Uniqlo last week with his sister Heidi to get smaller trousers for him, but they are still baggy.

5:55am In the living room where she now sleeps, I wake our snoozing elderly dog Lucy Rocket to take her downstairs for a walk. In the time before Leukemia, the early morning walk was Michael’s domain. Now he is not allowed to handle her at all, doctor’s orders. Dogs and transplant patients don’t mix well, but not as bad as plants and transplant patients. While we had to get rid of all the plants (non-negotiable), we made a deal for the care of the dog so she could stay. She’s almost 15 years old, semi-blind, mostly deaf, has no teeth, and two major (non-infectious) health issues. Finding a new home for her, even temporarily, would be incredibly hard on her. Not to mention what it would do to us! So we are being very strict about where she can sleep, bathing her regularly and washing her bedding every couple of days. It’s worth it, all of us agree. I have trained her over the course of the last year to not need a walk in the 5 o’clock hour, pushing her morning walk back to 8:00am. Today’s early wake up was a surprise to her. I feel you, sleepy girl.

6:30am Michael and I are eating breakfast and he’s taking his morning pill regimen, setting aside one drug which has to wait until after his blood test. They need to make sure he’s properly absorbing the medication, one of the most important post-transplant drugs.

7:00am Last night we’d packed up Michael’s hospital go-bag, filled with everything he needs for a day of sitting around the Out-Patient Clinic, plus a couple vital items should they need to admit him overnight. I toss an extra shopping bag into my backpack in case I have time to run errands. This is a brand new schedule and we have no idea what to expect. When I walked the dog, the skies were a gorgeous blue, so I pull the umbrella out of my backpack to lighten the load.

7:10am We board the internal bus for our beach community for the five minute ride to the North Plaza, where a taxi I’ve arranged is waiting for us. We’ve been told Michael needs to completely avoid public transit for up to a year post-transplant. This is one of the biggest lifestyle changes we’ve experienced since Michael began cancer treatment. I’m a vocal advocate of public transit and adore living in a place so well connected by buses, trains, trams, and ferries. I usually take a taxi 2-3 times a year, only when it can’t be avoided. Now I’m taking them 2-3 times a day. The internal bus for our beach community is unavoidable, however… No private cars are allowed in and taxis can only go as far as North Plaza, a 10-15 minute walk from our building if you’re strong and healthy, currently impossible for Michael.

7:15am Right on time the taxi pulls away. I’d found a taxi service with a negotiated flat rate to Princess Margaret Hospital when Michael was going through chemotherapy, and they also gave me a discounted rate to Queen Mary Hospital, a much longer distance. The metered rate is between $350-480 HKD ($45-62 USD) one way, depending on traffic, but the negotiated flat rate is $270 HKD ($35 USD) no matter how long it takes. The only drawback is it must be booked in advance and the internal bus system taking us to North Plaza’s taxi stand is unreliable… we often end up being 10-15 minutes early or late. Today it all worked perfectly. Whew!

7:45am The blue skies I saw at 6:00am while walking Lucy Rocket are gone, replaced by dark grey clouds currently pouring rain down on our taxi. I know better than to go anywhere without an umbrella in summer in Hong Kong, and I regret leaving mine at home.

8:15am Despite the rain, the taxi ride only took an hour. We slowly make our way to Registration on the ground floor of the Main Block. It’s the longest walk Michael has done since June 16th when he was admitted for the transplant. He sits while I take care of paperwork at the counter, then we make our way back to Block K and head up to the 8th Floor.

8:30am We hand over his paperwork, they give him a hospital bracelet, and then he is weighed and escorted back to a procedure room where they will draw his blood. We know he’ll need an IV medication today which takes four hours, but the tests will show if he needs anything else, like a blood transfusion. I sit in the waiting room with his backpack, waiting to find out if he’ll join me until his IV begins or if they’ll keep him back there.

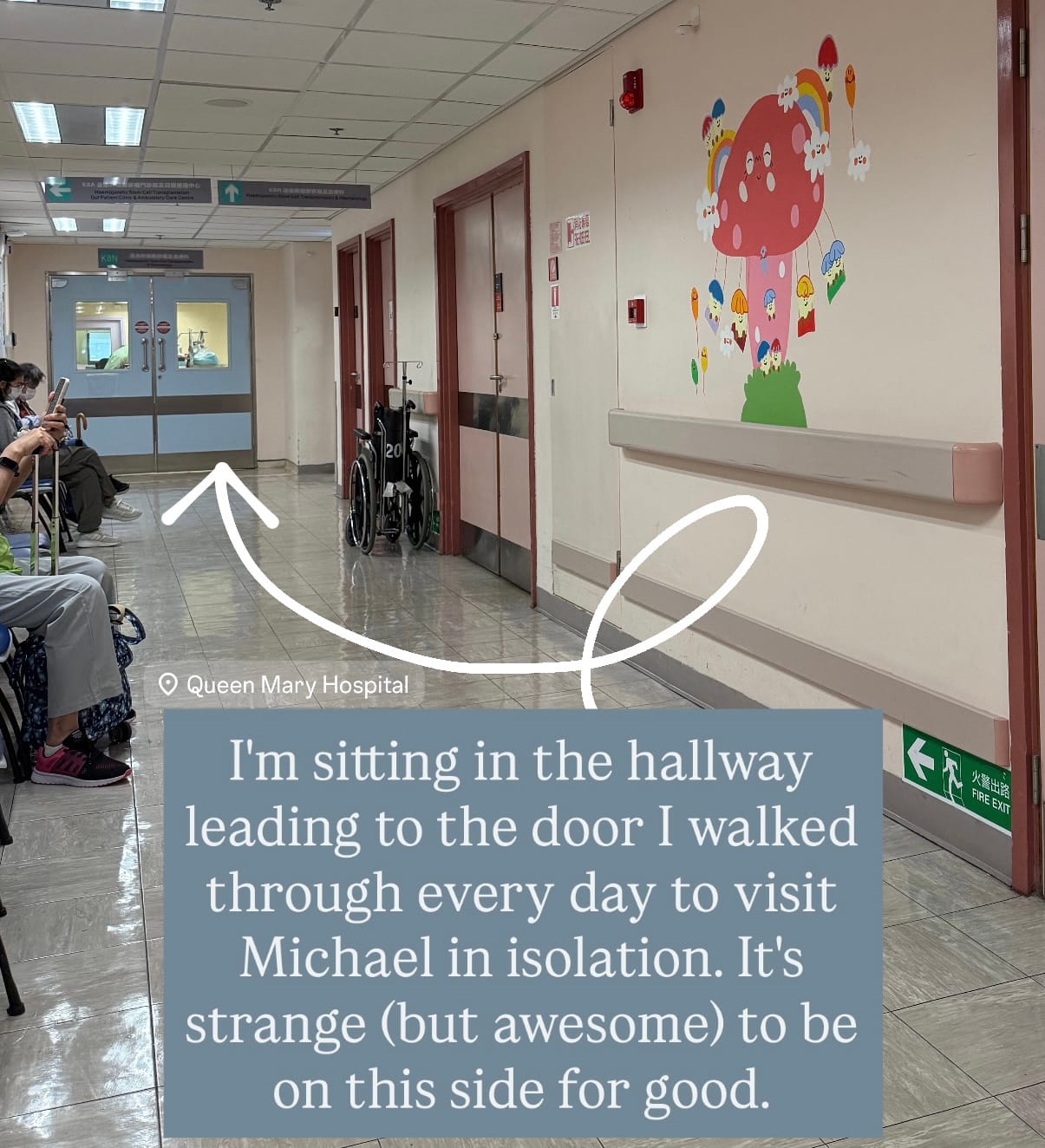

9:00am Michael texts me and asks me to come back and bring his bag. The nurse who did Benjamin’s stem cell donation is the one taking Michael’s blood today. She tells us both that she will give us a comprehensive orientation. She hands me a colorful piece of paper filled with all new information and tells me she’ll explain it all later. I ask when that will take place so I know what to expect. Should I stick around? Should I go run errands? She tells me it will be “soon” and to wait in the waiting area. There is no room for visitors in the procedure room. It has two beds, a line of patient chairs for those getting IV’s, and a bathroom. The waiting room has now filled up with patients, so I go sit in the hallway outside the Out-Patient Clinic, with a view of the double doors leading into the Transplant Isolation Ward which was Michael’s home for 67 days.

10:50am I don’t realize it as it’s happening, but anxiety has been creeping up as nearly two hours pass. I’m trying to read a book to distract myself but I’m struggling to sit still and focus. I keep noticing I’m clenching my jaw and holding my breath. Each Monday and Thursday, the Out-Patient Clinic is filled with post-transplant patients who line the hallway where I’m sitting and the waiting room of the clinic itself. For nine weeks I had to walk past this line of patients, all in varying states of ill health and reduced mobility. I never got used to it, it never got easier. Almost every time I passed I found myself holding back tears thinking of the individual journey each of these precious humans were on, while looking at a possible vision of our own future in this hallway. Now we’re here and it is just as difficult as I thought it might be. There is a pediatric ward here too, and occasionally a mama will carry her quiet baby or push a motionless toddler past me in a pram into the pediatric area. I can feel all the worry and fear radiating as they walk by, so I look into the eyes of every single mother who passes, saying a silent prayer for them: strength, strength, strength. Tears I’ve been holding at bay leak out. I text Michael and ask for an update… sitting here alone is not good for my mental health and I’m not going to make it four more hours here by myself if the nurse isn’t going to do the orientation shortly.

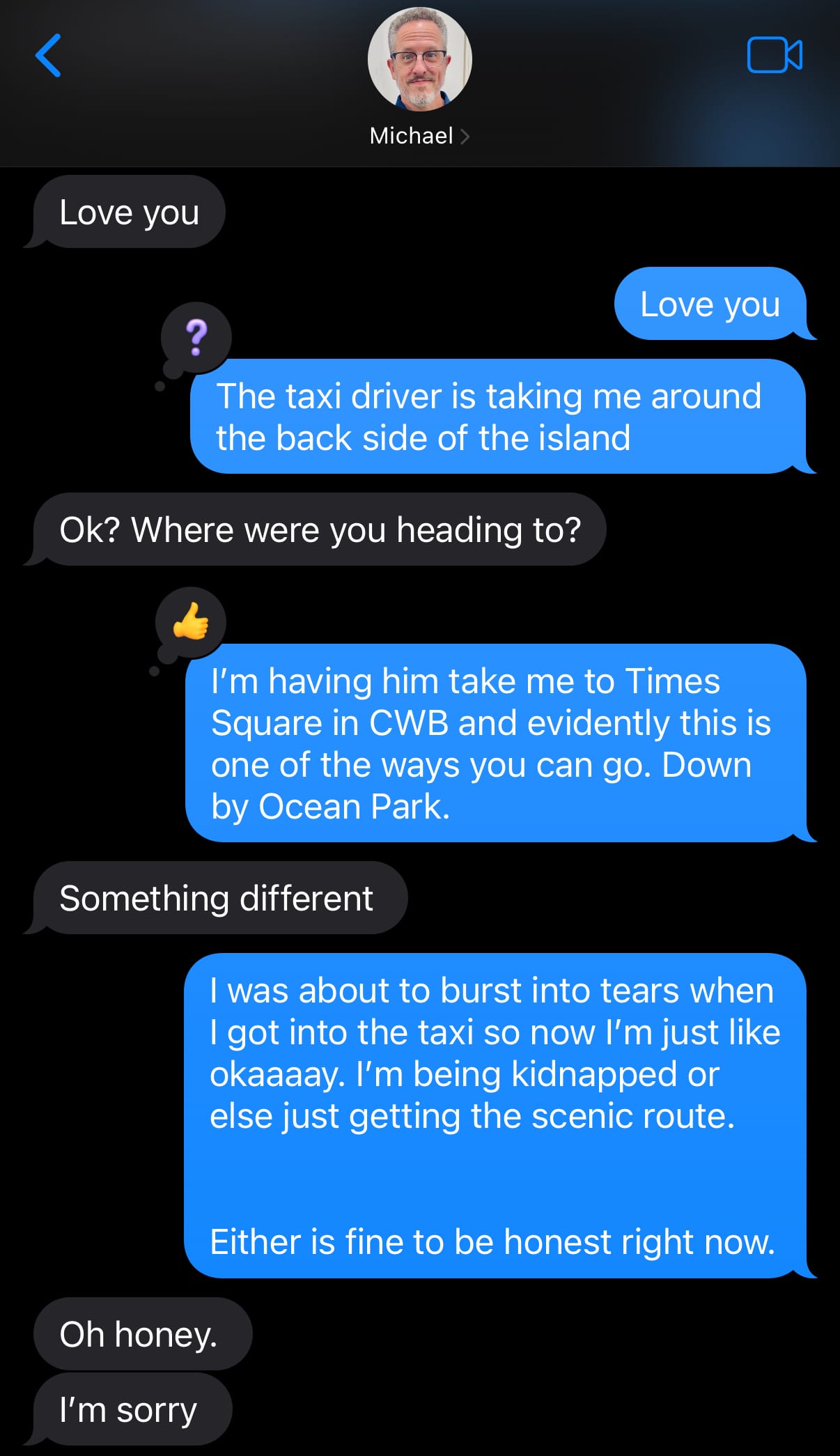

11:00am The medicine for Michael’s IV finally shows up and they start the four hour drip. The nurse tells him there is no need for me to wait, she can do the orientation at the end of the day. I’m shaky and try not to get upset… I could have (should have) left hours ago. I text Michael that I’ll go run errands now and race for the elevator and jog out of the building.

11:15am I get in a taxi and tell the driver the name of a big mall on the same island as the hospital which has a huge Uniqlo next to it. I need to grab Michael a few more pairs of trousers in an even smaller size and everything from Uniqlo also has a drawstring in the waist… handy when you’ve dropped over 50lbs (22kg) and have no fat, no muscles, let alone muscle tone. The driver surprises me and heads left out of hospital parking lot, toward the south side of Hong Kong Island. I don’t spend much time in this part of Hong Kong at all, and when I do, it’s exclusively via public transit, so I’m momentarily confused. At least it’s a good distraction!

11:30am Michael gets an unexpected visit from the doctor he saw every day in isolation who gives him the morning’s blood test results. Everything looks good, nothing to be concerned about except a potassium deficiency which the electrolyte drinks they asked him to drink each day don’t seem to be helping. They will prescribe him a supplement in addition. Six miles (10km) away, I order a cup of coffee, yogurt, and a croissant sandwich at a cafe. I realized I haven’t eaten in five hours and maybe part of the shakiness and emotional upheaval could be that. Eight months into this journey of caring for Michael’s health and I still cannot seem to get this one part of caring for myself right. I resist the urge to be harsh about it and instead pop on my headphones, curl up in a comfy chair far away from other patrons, and listen to a few chapters of an audiobook while I eat.

12:30pm I make my way to the big Uniqlo next door. We’re having daily high heat warnings in Hong Kong but the store is stocked for a level of cold weather we never get here. Sweaters, long underwear, heavy corduroy pants, winter coats… yep, it must be August. All the lighter weight clothing is relegated to a tiny corner and there’s nothing left in Michael’s size. He’ll need to wear long pants, long sleeves and a hat when he leaves the house for the next year or so. During the daytime, sunglasses are now a must. All of this is to mitigate the risk of known side effects which come with the treatments he’s had, including the transplant itself. He’s now more prone to other types of cancers, especially skin cancer, and he’s likely to get cataracts which the sunglasses may protect against. There’s a new disease spreading through mosquito bites in this region, Chikungunya Fever. His team of doctors have impressed upon us the deep importance of prevention. So long sleeves, long pants, and a hat are a must for both sun and mosquito protection.

2:00pm I spend ninety minutes in the store (way too long) trying to make strategic decisions and end up getting three pairs of trousers for Michael. He’s always cold now, so the heavier fabrics may actually help. It’s hard to know how long it will take for Michael to regain any weight, and he’s not allowed to re-wear any clothes without washing them first — gone are the days we’d wear our jeans a few days before tossing them in the wash. With only two pairs of long pants which currently fit him, it’s a ton of pressure to get them washed and dried along with all the other things that must be washed daily (towels, wash cloths, bath mats, pajamas) while managing other things that must be laundered several times a week (sheets, mattress pad, duvet, duvet cover, the dog’s bedding and blankets she’s allowed to sit on) or month (curtains, couch cushion covers). Buying three more pairs of trousers which might only fit a month or two depending on how quickly we can increase Michael’s appetite, strength, and weight actually feels like a smart investment in this moment. My head is pounding and once again I notice I’m clenching my jaw and holding my breath. I go outside to just stand still and breathe deeply, feeling grateful it’s no longer raining.

2:15pm Michael tells me there’s a prescription I can go fill at the hospital pharmacy, so I hop in another taxi to head back to the hospital. This time the driver asks if I want to go through Central or through the tunnel to the south side of the island and I feel proud that I know what he’s talking about, but don’t know how to answer. Your choice, I tell him. He sighs and tells me it’s busy either way. I put on my headphones, lean my head back, and listen to a few more chapters of my audiobook with my eyes closed.

2:35pm I’m back at the hospital and run into the husband of one of the patients who was in the Isolation Ward at the same time as Michael. Through a few conversations over the last several months, I learned his wife had a bone marrow transplant eighteen months ago, and had been re-hospitalized at the same time as Michael for more chemo. There’s a bit of a language barrier so I had been unsure if that meant a relapse of Leukemia or was simply a preventative measure. She was released at some point while Michael was still admitted, so I haven’t seen him around. I greet him like an old friend, but my cheery face quickly changes when my question about how his wife is doing is answered with less-than-cheery news. She’s not doing well, she’s back in the hospital once again, it’s not good. I don’t pry into specific details, I just offer words of support and encouragement. He offers them right back to me. This is a weird club to be in, and I’m reminded that you can do every possible thing to treat this stupid cancer and it still might not work. Some people go on to live long healthy lives, some don’t. I say goodbye and make my way back to the eighth floor hallway. I sit at the far end by myself and have a small cry… I’m grateful we’re in Hong Kong, a world leader in blood cancer research, but I’m sad we’re in need of having to benefit from all that research in fighting blood cancer.

3:00pm Michael is finally disconnected from his IV infusion and I wait with him for the nurse to give us the orientation we were promised early this morning. There are so many differences from being a patient in the Transplant Isolation Ward and even from the Day Ward at Princess Margaret. While he’s in the Out-Patient Clinic here I can’t see him… at all. No visitors in the treatment area. It was a fluke that they let me walk back there this morning to hand him his backpack, we didn’t know it wasn’t allowed. It will be a huge adjustment. At Princess Margaret we used to hang out together all day when he had treatments in the Day Ward, and in Isolation at Queen Mary there were set visiting hours. Now my job is just to bring him to and from appointments. There really isn’t enough time to go all the way home and back again while he’s in the Out-Patient Clinic, so at least twice a week I’m going to need to find an uncrowded place to hang out for several hours, preferably a place where I don’t have to spend any money. The orientation with the nurse lasts twenty minutes. There are so many details my head is spinning. Thankfully, she has done this a long time, sees our panicked eyes, and kindly reminds us the staff is here to guide us as needed. I think of my text to Ben, about looking back on this day and laughing at what amateurs we were. I don’t feel especially confident that we will ever be able to manage this new schedule and routine with ease and grace, or at least with no tears. I write this down: This is not any easier. But we will get stronger.

3:30pm Michael’s hospital bracelet is cut off and we head down to the first floor pharmacy. One of the nurses from the Isolation Ward rides down in the lift with us. He’s so genuinely pleased to see Michael up and moving. I get a lump in my throat, once again flooded with gratitude over the support and care of everyone here at Queen Mary Hospital. The lump turns into actual tears when I see Michael’s crumpled face after I find a spot for him to sit so I can go run around the corner to the crowded hospital pharmacy. Weak and overwhelmed, he’s crying because he’s tired and hungry. His diet is so restrictive and we definitely did not bring enough for him to eat over the course of a ten hour day away from home. He’s shaking quite hard. I tell him I’ll turn in the prescription slip then run downstairs to the 7-11 to find something safe he can eat.

3:35pm I do everything wrong at the pharmacy. I wait in the wrong (long) line only to be told they don’t need the papers I gave them, nor do they need his Hong Kong ID card, things I always had to present first at the pharmacy at Princess Margaret Hospital, a place which was so foreign and confusing at first, yet find myself suddenly missing because it’s familiar and easy to navigate. Instead of the usual dozens at Princess Margaret, there are hundreds of people waiting here, everyone is coughing, lines snake around the room, there are constant announcements in Cantonese, and everyone is listening to something on their phones without headphones. Once the prescription is finally turned in at the right counter, I head down to the ground floor to scour the empty shelves of the 7-11. Lunch hour at the hospital is from 1-2pm, and now it’s after 3:00, so everything I would normally grab for Michael is gone. I start reading ingredient lists to check for all things he can’t have, rejecting more than I keep. Three possibilities in hand, I climb the stairs back up to the place I left Michael, away from the huge pharmacy crowds. Nothing is especially appetizing to him and I see the disappointment in his eyes. He gives everything a try anyway. When his medicine is ready I return to collect it, this time in the right line, which is relatively short with only a dozen people ahead of me. Michael isn’t strong enough to take the stairs, so we queue for the slow elevator to go down one floor. I can’t get the negotiated rate with the taxi company this time of day, so I call an Uber as I have a small coupon I can use. The fare home is $325 HKD ($42 USD).

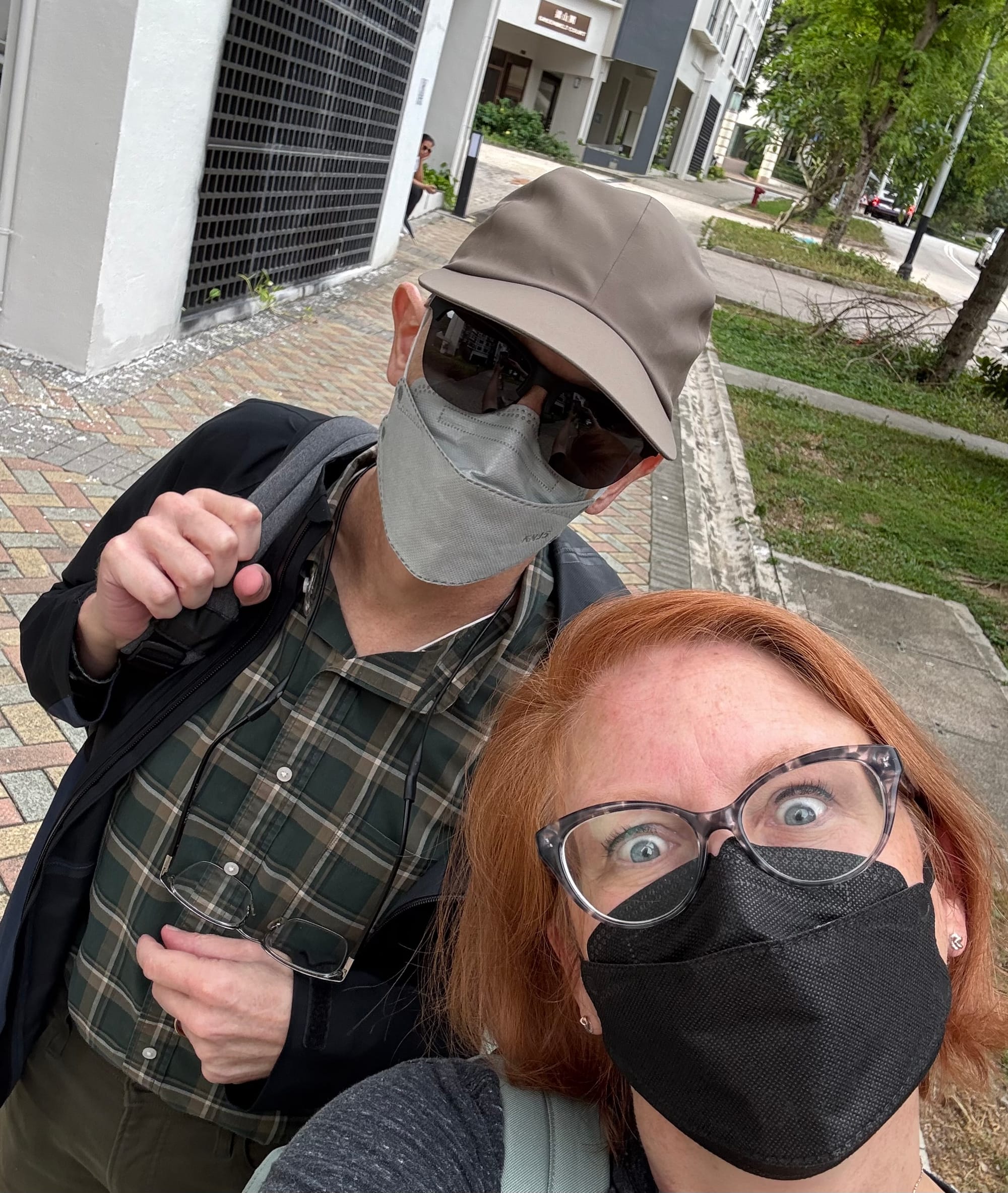

3:55pm We begin the journey home. No rain, so we get back to our little beach community in 45 minutes. We wait for the internal bus, which is packed with uniformed school kids. Every one seems to be coughing and I pray for a supernatural force-field to protect us from whatever is going around. I put Michael in one of the priority seats moments before the bus lurches away. An elderly woman gives us the stink eye and I realize I’m simply going to have to grow thicker skin. Standing up on the moving bus won’t be possible for my sweet husband for some time.

4:50pm We arrive back at our building, ten hours after we left. I take a selfie to send to the family group chat and don’t retake it even though my eyes are crazy. It’s been a long day, clearly.

5:30pm I start making dinner, beyond grateful I’d wisely done a ton of prep on Sunday afternoon. All I need to do is start the rice cooker and cook the chicken.

5:35pm Michael gets a call from the Out-Patient Clinic. They tell him one of his test results just came in and they’d like him to come back and pick up another prescription for a stronger dose of the most important medication he’s taking to keep his body from rejecting the transplant. He tells them we just got home, it would be a three hour round-trip journey to do what they are asking. They are insistent for a few minutes, then finally tell him he can come back tomorrow if he can double up on the stock he has that was meant to last until Thursday. He has enough for this evening’s dose and tomorrow morning’s dose. We sit on the bed and just stare at each other. Then we gather the boys and brainstorm with them over how to get the medicine (both of them will be on Hong Kong Island the next day, so one of them can pick it up and bring it home before he needs to take the evening dose) and how to make these incredibly long days easier. Everyone comes up with a helpful idea and we decide we’ll implement all of them for Michael’s next long day at the Out-Patient Clinic on Thursday. We put on a brave face and remind ourselves we’re new to this right now but won’t always be.

6:00pm We sit down together as a family and eat dinner, a rare occasion that hasn’t happened much this year between hospital visits, work, and school. Everything I made is safe for Michael to eat on his restrictive diet and it’s nice to not need to change a single thing for him. After noting there is nothing left over, I decide this will go into rotation to cook for the long days at the hospital. After dinner we repack Michael’s hospital go-bag just in case he spikes a fever in the night and we have to make a run to A&E, I do a couple loads of laundry, we both shower, then get ready for bed.

9:30pm Neither of us can keep our eyes open any longer. We lay in bed facing each other, quietly chatting about how this new phase has such an incredibly steep learning curve. I repeat again that although this isn’t any easier, we will get stronger. We turn out the light, grateful tomorrow is already on its way.

Like this content and want to support more of it? Consider a one time contribution at Buy Me A Coffee. Thank you and have a Plucky Day!