Plucky Hard

I needed a lot of pluck this week!

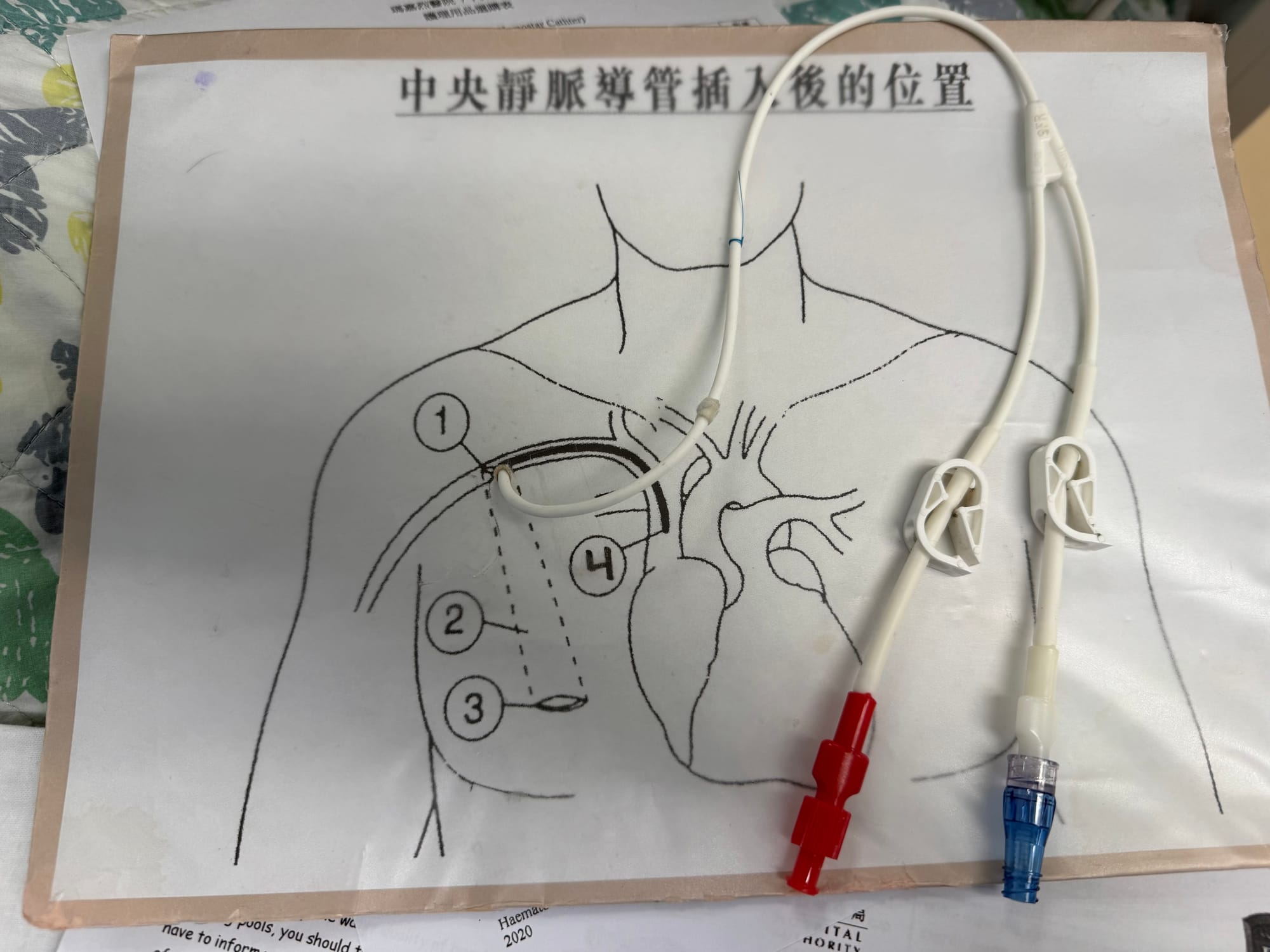

I did something hard on Monday. I was scheduled for surgery to install a Central Venous Catheter (CVC, aka Hickman Line) in preparation for my bone marrow transplant. The PICC line in my arm did not have a large enough bore (tube diameter) to receive the transplanted stem cells, so before my admission to Queen Mary Hospital later this month, I needed to have a procedure to remove the PICC line and install the Central Venous Catheter.

I was admitted into the hospital on Sunday morning, quite nervous and scared of the procedure. They checked my blood pressure and temperature, triggering my anxiety over what happens when the reading is at 38C (100.4F) or higher. This time, all good news… no fever. After some waiting they came to meet me with a stack of consent forms and an explanation of what the Hickman Line procedure would entail. It was scheduled for early Monday morning.

Later on Sunday they came to remove my PICC line (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter). My PICC line was installed New Year’s Eve before beginning chemo. They insert a tube into a vein in your arm (close to your elbow) which runs up your arm and into your heart. This is a longer term replacement for an IV in your hand, which is generally only good for a few days before the vein swells and causes pain or infection. The PICC line is used to administer medication, chemotherapy, and to take blood samples. There were instructions for care and protection when I shower and plus daily hygiene to keep it in place and protect me from infection. That was scary then, but Heather and I managed, learned, and adapted to this new thing hanging out of my arm — jokingly calling it my “dangly bits.”

Every seven days my PICC line had to be purged and flushed to make sure my blood wasn't coagulating in the line, blocking the flow in and out. They also had to carefully change the many layers of dressings and clean the skin under the bandages. The dressings were a four-part bandage, securing the line to my arm, sealing it from air and moisture while maintaining a sterile environment. The line had a direct access to my heart, so tons of care was needed in cleaning and dressing.

When the technician came to remove the PICC line at my hospital bed, he didn’t remove the dressing layer by layer as I’ve been used to the past five months. Instead he peeled the whole bandage system away from my skin in one go, then pulled the 60cm (24”) line directly out of my arm. It happened so fast I don’t remember feeling anything. A nurse covered the now open wound with gauze and heavy bandaging.

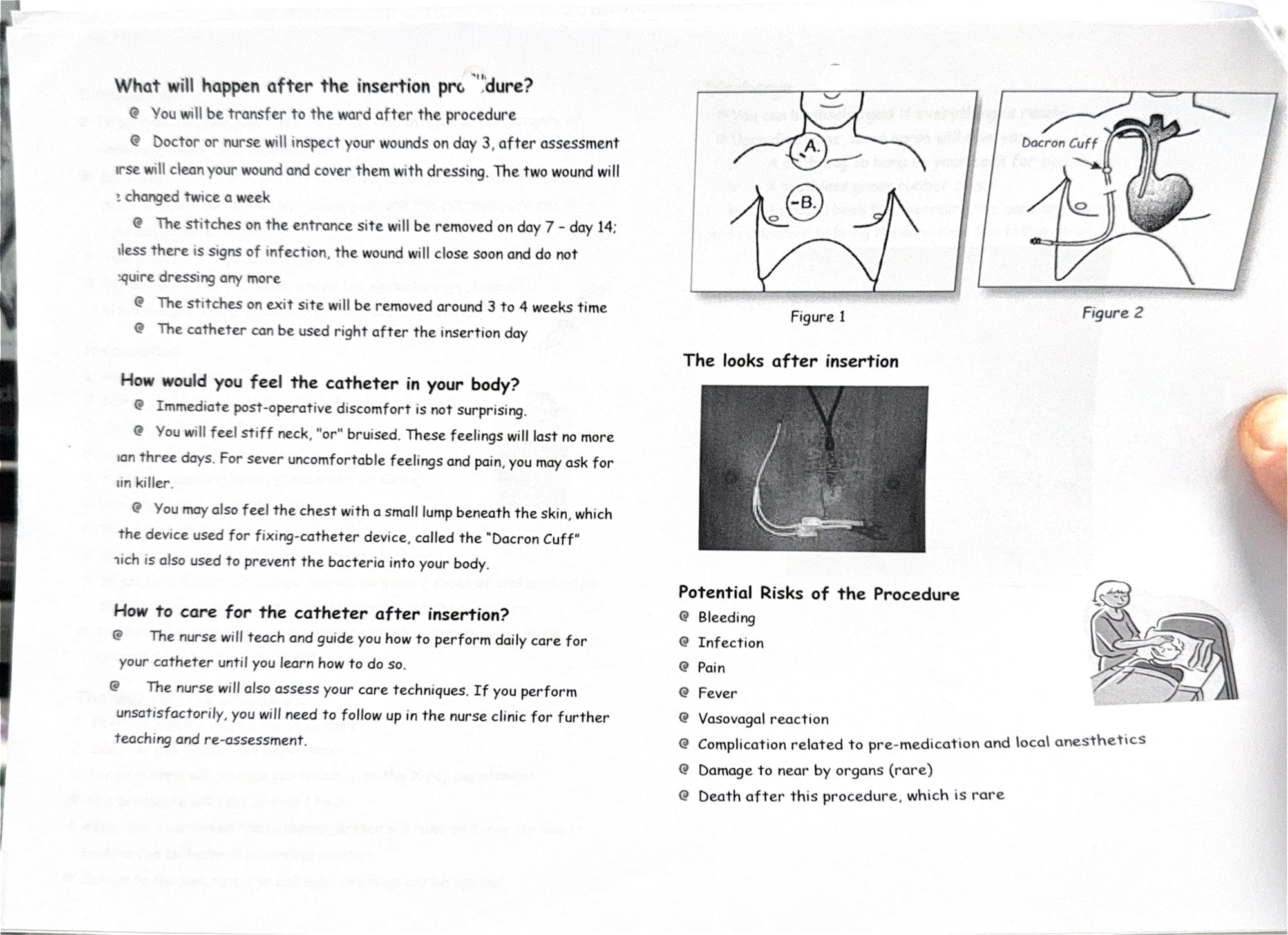

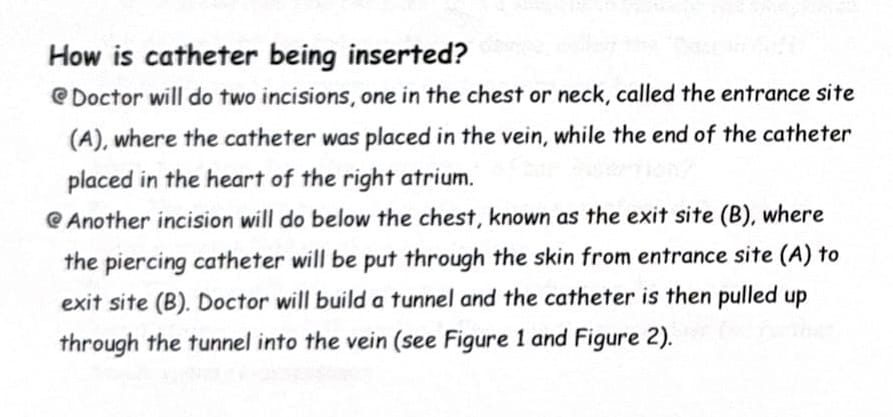

After my PICC line removal, it was time to learn about the upgrade I would get the next morning. I was given an English printed pamphlet for the CVC / Hickman Line, and a cardboard mounted diagram/model.

After reviewing the pamphlet a few times, the nurse gave me a surprise verbal test, to make sure I understood the risks, hygiene and care, and when I should return to hospital when or if something goes wrong. A big risk is accidentally cutting or puncturing one of the tubes hanging out of me, so I was taught how to use a plastic clamp to seal it off and then which hospital to rush to for repair or replacement under surgery again. During the test she was very stern with me, making certain I clearly understood what my role was in caring for my catheter.

Afterward, they explained they would take me to the radiology surgical theatre to perform the procedure at 8:30 a.m. Monday morning. So there was nothing to do but sit with my uneasy thoughts all night.

Morning finally arrived. I freshened up in the bathroom after the nurse checked my blood pressure and temperature once again. I had to fast four hours prior to surgery, so a little before 8:30 a.m. they whisked me and my empty stomach off to another block in Princess Margaret Hospital, wheeling me down the sidewalk and through the labyrinth of hospital wards on a gurney. I had to leave all my personal items behind, including my phone, glasses, and wedding ring.

I’d been nervous about the procedure, trying to keep my mind distracted, but now that it was happening, my anxiety started pinging. I was placed in a hallway outside the operating room to wait my turn. Each time the door would open, I could see the operating table, and a bunch of high tech equipment I wasn’t familiar with.

Throughout this year my back has had a lot of pain. Loss of muscle, less activity, and the cancer in my bone marrow have all contributed. Laying flat on a hospital bed doesn’t help, and that morning it was already hurting quite a bit. Once they transferred me to the operating table, it got so much worse. They put towels under my head and told me to turn it to the left to expose my neck, to remain still, not moving during the procedure.

As they prepped all of the equipment and the tables, the surgeon came to discuss the procedure with me again, in much more detail, informed me of all the potential risks again, and had me sign the consent forms. I asked the attendants if they could put a rolled up towel under my back where it was hurting, but it didn’t help. They set up a large monitor for the live X-ray viewing of my neck and arteries, and the surgeon took a sonogram of my neck to measure and see the artery he wanted to place the catheter into. It was all so overwhelming. I had a bit of an anxiety attack and found myself crying while trying to lay still to let them prep me.

There was an issue with the paperwork and consent forms, as the paperwork said they would do the insertion on the left side of my neck. The doctor wanted to go in on the right. Apparently they almost always insert it on the right with a much more direct route to the heart. The left side has more bends and turns, making it more difficult. So the entire staff left to redo all the paperwork for me to sign again. This left me alone for what felt like half an hour, giving me more time to cry and panic.

Finally they were ready to start the procedure. They had me turn my head to the left, placing a sheet over my head with a cutout around my neck area for the two small incisions. Having a sheet covering my head did nothing to alleviate the panic and anxiety I was already experiencing.

Making things worse was the fact that I am profoundly deaf in my right ear. I usually sleep on my left side with my good ear on the pillow to completely block sound. With my head turned to the left, my good ear was blocked under my head, pressed against the towels on the table. I couldn’t hear any of the instructions the doctor gave me. I had to call out to remind them of my deafness. They used a small stand to prop up the sheet directly in front of my turned face, and a nurse would duck her head down under the sheet to relay information from the surgeon to me. Fun, huh?

(Content warning: description of surgery from my viewpoint in this paragraph.) They gave me a few shots of local anesthesia in my neck then started the incisions. I could feel blood rolling off my shoulder. The longest part was the first incision in the neck and whatever else they did there with the artery. Once that was stable, they made the second incision lower to insert the catheter and join it with the artery from the first incision. During this part I was instructed to hold my breath and be as still as possible. It took about 30-45 seconds for them to make the connection, yet I still held my breath for probably a minute longer. They took a live X-ray to make certain everything was where it was supposed to be, then stitched up both incisions and cleaned me up, applying gauze and bandages over the wounds.

After transferring me back onto the hospital gurney, I was rolled into the X-ray room for a static chest X-ray to make certain the CVC had not punctured a lung. When everything looked good, I was returned back to the Hematology ward to retrieve my glasses, wedding ring, and phone with all the messages from Heather. I called her at 11:00 a.m. The whole journey, start to finish, took two and a half hours.

Heather arrived at 4 p.m. to meet with the head nurse for an in depth, hands on lesson in how to care for and clean my new Hickman Line, including how to take a shower with it, keep it clean and safe, and what to do in an emergency if it gets cut or punctured. We received a small supply of cloth pouches to hang around my neck to keep the dangling catheter parts from being damaged. These must be washed and ironed (high heat sterilized) each day, another new thing to get used to.

The hospital staff kept referring to my upcoming time at Queen Mary Hospital, and the new routine of self care and hygiene which comes with both the Hickman Line and the bone marrow/stem cell transplant. It’s a lot. Like everything else this year, it will be another difficult set of things to get used to which initially appear to be impossible but then fade into a strange new normal.

When I first got my PICC line, it was a hard, scary thing. I’ve never had something like that before. This new Hickman Line is a step up, and it seems more intense and scary than the PICC line. Yet all we learned through the five months of care and management of my PICC line made us stronger. It was training for the Hickman Catheter. Right now it feels new and scary, but we can already see how far we’ve come since New Year’s Eve when I got the PICC line. We’re stronger, more courageous, and know that we can do uncomfortably hard things because we’ve done them before.

Looking ahead to the bone marrow transplant is terrifying. Honestly it’s scary as hell. It makes all the chemo treatments and radiation treatments I’ve had so far feel like child’s play before the real thing. It will be long, six to eight weeks of really awful stuff in a cold, sterile transplant isolation room. When I shared with one of my doctors that it felt like everything else was just practice for the main event, he reminded me just how difficult everything I’ve already done has been. It’s been a long series of main events, and every one of them has made us stronger in so many ways, preparing us for the next one. It’s still scary, it’s still hard, but we’ve got pluck and will continue on, one foot in front of the other, through the darkest parts of this journey. We are hopeful and confident that the best is yet to come.

Wishing you a plucky day with whatever you might be facing!

Enjoying these posts and want to help fund more of this content? Consider sponsoring our efforts through Buy Me A Coffee. The money goes toward a less caffeinated but still necessary taxi ride to the hospital for treatments. Thank you for your support and we hope you have a Plucky Day!